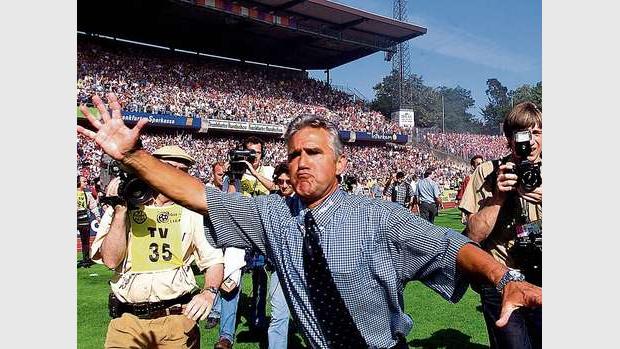

It’s match day 10 of the 1996/97 Bundesliga season. The Parkstadion in Gelsenkirchen is packed to the rafters once again, but the fans aren’t in a good mood. During the speaker’s line up call the fans show their dismay for the club’s treatment of Jörg Berger. The coach had been successful at the Royal Blues for the last 3 years, but the players wanted to get rid off him in the end.

As the speaker called out the first name of the players in the starting line up. the fans reacted by shouting Berger’s name, louder and louder every time a player’s name was called out. “He spent more time in the sauna than on the pitch”, was one of the players accusations.

His dismissal at Schalke was a rotten betrayal according to the fans. However, Berger himself reacted calmly to losing his job. He had, after all, been through much more hardship during his life.

From talent to coach

After finishing school in the GDR, Berger envisioned a career as an architect. However, his talents on the football pitch had become apparent and the young striker decided to play football for a while. In 1964, the 20-year-old Berger joined SC Leipzig trying to make it as a footballer, but after three years on the pitch the youngster had to throw in the towel as a player, as injury prevented him from pursuing his footballing career.

Instead Berger chose to become a coach at a young age. After taking his coaching license in Leipzig, Berger worked as a youth coach at Lokomotiv Leipzig and Carl Zeiss Jena. After a two year stint as the coach of Hallescher FC, the talented coach was hired to become the national team coach of the GDR’s U19 side back in 1976.

In the same year, Berger decided to get a divorce from his wife. Furthermore, the coach also brushed off numerous requests by the Stasi to work as an informant. Given his status as a bachelor, and the fact that he wasn’t willing to work with the authorities, the Stasi became suspicious of him.

After a while Berger was denied permission to travel with his team to international matches in Western-European countries and when the coach asked a Stasi official what he should tell his players, he was told:”Tell your players that your father is dying and that you need to stay at home.”

Despite these hurdle,s Berger was promoted to become the coach of the GDR’s B-national team in 1978. This didn’t decrease the pressure from the government workers who spoke to Berger on a regular basis. The coach remembered in an interview:

“I was pressured to get married again. I was in a situation where I told myself:’You can’t live like that for the next 30 years.’ I wanted to take my own life into my own hands again.”

Fleeing the GDR

Despite hating the system, Berger lived his life normally. “If I had planned anything, I might have gotten caught”, he would later say. Instead he fled his existence by engaging with “wine, women and song”. However, in 1979 Berger eyed a chance of making it out of the GDR and over the boarder.

The coach was given permission to follow the national team’s B-side to an international match in Yugoslavia. At that moment it became apparent for Berger that it was now or never. During his last visit to his parents, the former striker told his mother about his plans. Being afraid of being listened to by the Stasi made Berger take the precaution of telling her about his plans on the top floor of his parents house.

On the night before the match, Berger left his hotel room at three o’clock in the morning, whilst everybody was asleep. The team were playing in Subotica, and all the coach wanted to do was to get to Belgrade.

In his shoe Berger hid a train ticket for the night train to Belgrade. After arriving in the capital he made his way to the West-German embassy. At the embassy Berger was given a forged passport, which enabled him to take a train from Belgrade to Austria.

In Berger’s absence the leader of the GDR’s delegation, Wolfgang Riedel, had contacted the authorities which meant that Berger was a hunted man whilst he was still in Yugoslavia.

Gerd Pensei was the name the embassy had put into his forged documents. Before the train was allowed to cross the boarder from Yugoslavia to Austria, Berger had to live through some nervous moments. At the border his passport was taken in by an uniformed police officer, but after a while the officer returned, handing over the paper, saying in broken German:”Have a good journey, Herr Berger.”

If it had been a different police officer on border patrol this day, Jörg Berger’s life might have turned out very differently. Back in 1979 the GDR and Yugoslavia had an agreement that persons trying to flee East-Germany should be handed back by the Yugoslavians. After the train crossed the boarder into Austria Berger felt relief and a moment of enormous joy. He put his head out of the train window and screamed at the top of his lungs for one brief moment. Berger had successfully fled the system he hated so much.

The Stasi keeps watching

Years later Berger would still say that it was the right decision. He told Zeit: “You can’t imagine how difficult this is. Pushing myself to do what I did, still makes me proud to this day.”

However, he wouldn’t hide the fact that it wasn’t an easy decision either. Fleeing the communist regime in the east meant that he had to leave behind his son, who was 8-years-old at the time. His son would have to go through hardships of his own in the GDR due to the fact that his father had fled the country.

After arriving in the west, Berger was met with shut doors. Before he left his life behind, his mother had warned him:”Don’t expect them to have waited for you over there!”

Finding a new employer was among the coach’s top priorities. However, this was made harder by the fact that the DFB demanded that he should take his coaching license all over again. Despite the fact of his extensive work on the other side of the border.

Furthermore, it took only one week before the Stasi had found out where Berger was living. At first the secret service of the GDR tried to lure him into a trap by sending two of their officers to approach him on the street. Berger was told that his mother had made it to Sweden and that she wanted to meet him.

After joining Hannover 96 in 1986, Berger’s health suddenly deteriorated. He felt a tingling in his toes, was nauseous and suffered from fever. Berger didn’t approach a doctor and soon had difficulties walking due to his body’s weakness. Test after test was commissioned, but no answers were found.

Only after four years was the answer to his problems found. According to Dr. Wolfgang Eisenmenger the coach was most likely poisoned with lead and arsenic. Additionally Berger had to live through several episodes of his car’s tires being torn up. Another episode from those years saw a tire of his car coming off as he was driving along on the Autobahn at a pace of 160 km/h.

All in all there were 30 to 40 people who had taken a closer look at Berger according to the coach. His Stasi files confirms that there were 21 people who had contributed to the data collection.

Friendships and trusts that were broken

After taking a closer look at his Stasi files Jörg Berger was shocked. A good friend of his, a skiing and camping buddy, had told the Stasi about his dealings. “If I had told anybody about my plans to leave, it would have been him”, Berger would late say.

Another man who he had a close relationship with was Bernd Stange. The current coach of the Syrian national team worked closely with Berger in the youth department of the GDR. In 1984 Stange contacted Berger from a hotel in Luxembourg, having a chat with him. In his Stasi file the former Eintracht Frankfurt and Schalke coach found out that Stange had been working closely with the Stasi.

The goal of Stange and the Stasi was to bring Berger back into the GDR. In the end Berger’s caution paid off, as he didn’t fall for any of the tricks used by the GDR’s authorities. In his book “Meine zwei Halbzeiten” Berger would later reveal that he couldn’t forgive either men for their actions.

Another man Berger should meet later on in his life was Wolfgang Riedel. The man who once had tried to get the Yugoslavian police to stop him from fleeing the GDR. Riedel was believed to be a man who was loyal to the GDR system, meaning that he wouldn’t have been troubled by what would have happened to the likes of Berger if they had been caught.

The DFB didn’t care too much about Riedel’s checkered past and later appointed him treasurer of the North-East German football federation.

Death and legacy

Jörg Berger died on June 23rd in 2010. After his arrival in Germany he had worked as a coach at many clubs, often times saving teams from precarious situations. During his years in the Bundesliga, Berger spent time at eight different clubs and was appointed head coach at a Bundesliga club on nine occasions.

His three year long stint at Schalke 04, which saw him lead the team from the brink of relegation to the Uefa Cup, made him a vital part of the club’s history during the 1990s. Furthermore, most Eintracht Frankfurt fans remember the coach for his work between 1988 and 1991 and for saving the team from relegation back in 1999.

Berger’s last big success came when he led Bundesliga 2 side Alemannia Aachen to the DFB Pokal final in 2004.

Love reading historical accounts of former GDR players or coaches and how they managed to live through this awful time of being ‘bespitzelt’.

Much, much respect belongs to Jörg Berger.